Analyzing the Artificial Structure of English Royal History

This article proves that English royal history is a later fabrication, supporting the findings of Edwin Johnson. It presents several artificial patterns as evidence: 1) A recurring algorithm where every seventh king is named Edward. 2) Dynasties arranged in fixed numerical blocks of 8 and 4 rulers. 3) Three consecutive dynasties (Lancaster, York, Tudor) each containing exactly three kings. 4) Impossibly identical reign durations, such as the combined reigns of the Lancaster Henrys and Tudor Henrys both totaling exactly 62 years. These structural and numerical regularities are statistically improbable and suggest the official timeline is not a genuine record but a meticulously fabricated narrative.

CLASSICS

10/7/20254 min read

The official narrative of English history, with its sprawling timelines and complex dynastic shifts, is traditionally accepted as a genuine record of the past. However, a deeper analysis reveals startling structural regularities and numerical patterns that defy the chaotic nature of real historical events. Drawing on insights from historical critics like Edwin Johnson and detailed numerical investigations, a compelling case can be made that much of England's royal history, particularly from the early medieval period to the dawn of the Tudors, is a later invention—a meticulously constructed narrative rather than an organic progression of events.

The Echo of Edwin Johnson: History as Invention

This investigation begins by echoing the radical findings of Edwin Johnson, who, as early as the late 19th century, argued that a significant portion of early English history, specifically from approximately 700 to 1400 AD, is a later invention. Johnson's work posited that chronicles were often backdated, merged, or entirely fabricated, creating a dense but ultimately artificial historical record. The patterns we are about to explore lend strong support to this controversial thesis.

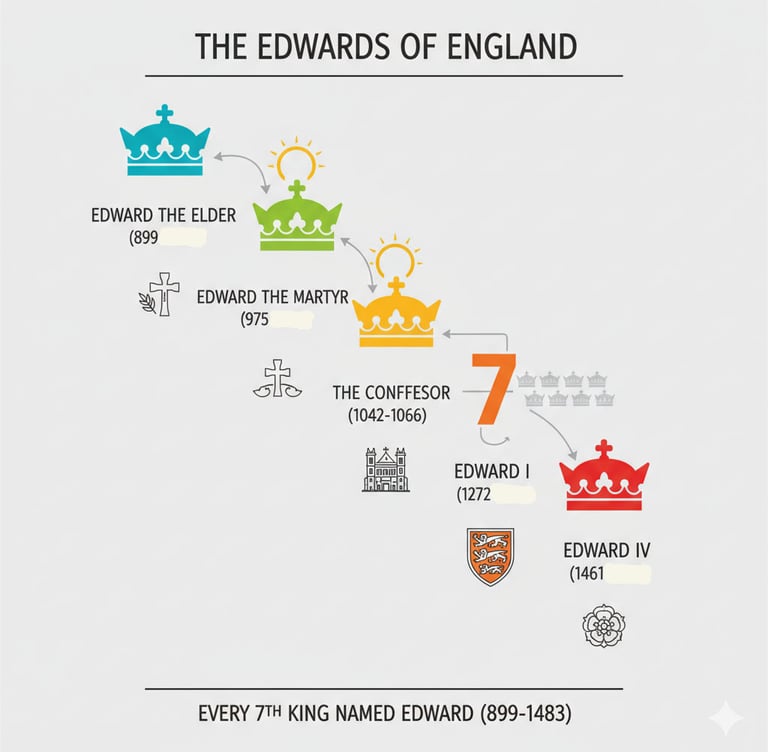

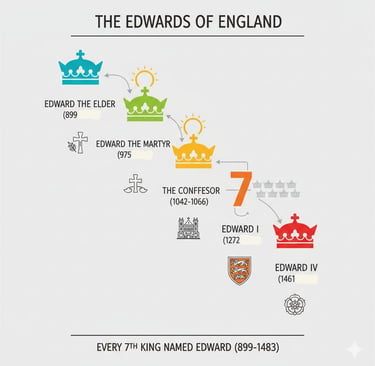

The Edwardian Algorithm: Every Seventh King

One of the most striking patterns emerges when examining the succession of kings. If we temporarily treat the Norman period (1066-1154 AD) as a distinct, perhaps interpolated, block, a remarkably consistent algorithm appears:

From 899 AD, every seventh king in the succession is named Edward, a pattern that holds precisely until Edward IV ascends the throne in 1461.

This recurring septennial naming convention for such a long and turbulent period is statistically extraordinary. It suggests a deliberate structuring of the king list, where names were assigned to maintain a symmetrical, almost ritualistic, sequence.

Dynastic Blocks: A Programmed Succession

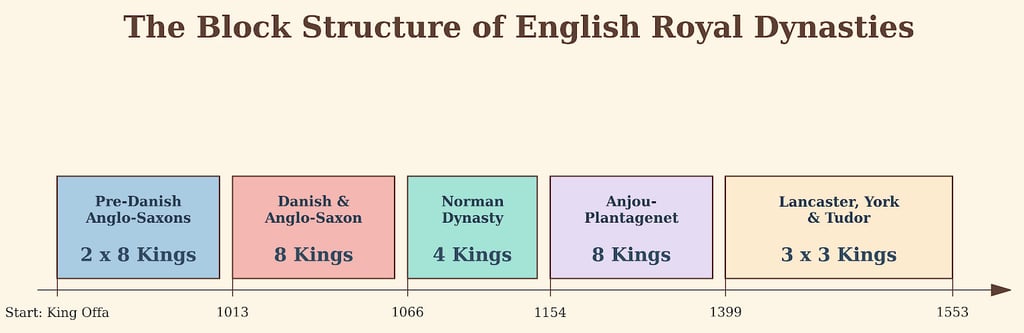

The artificiality of the royal lineage is further underscored by the way entire dynasties are arranged into fixed, numerical blocks of kings. This "block programming" of history is highly uncharacteristic of natural succession.

Consider these precise arrangements:

The earliest period shows two consecutive blocks of 8 Anglo-Saxon kings each. This neat division into identical numerical units of rulers points to an organizational principle, not random historical development.

Following these, there is a distinct block containing 4 Danish kings, immediately followed by another block of 4 Anglo-Saxon kings.

This is succeeded by 4 Norman kings, maintaining the exact block size.

Finally, the long and influential Anjou-Plantagenet dynasty is presented as a block of 8 kings.

The consistent use of blocks of 8 and 4 kings across different dynasties and centuries is a powerful indicator of a constructed historical framework.

The Triple Crown: Three Dynasties, Three Kings Each

The numerical precision continues into the late medieval period, signaling another phase of intentional arrangement.

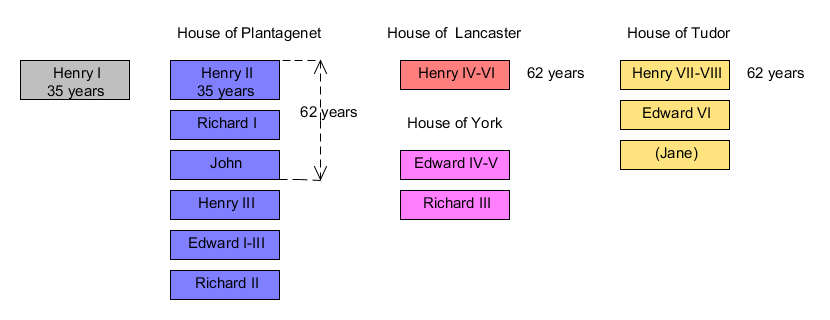

After 1399, English history presents three consecutive dynasties, each perfectly containing exactly three kings:

The House of Lancaster had precisely three kings.

The House of York also had precisely three kings.

The foundational House of Tudor likewise had precisely three ruling monarchs (Henry VII, Henry VIII, Edward VI).

The chances of three major, consecutive dynasties each naturally producing exactly three kings is exceedingly low. This symmetry strongly implies a narrative convenience, where the number of rulers was adjusted to fit a predefined structural requirement.

Reign Lengths and Combined Durations: Impossibly Identical

The final pieces of evidence come from the duration of reigns and combined dynastic periods, which exhibit an impossible identicality:

The first two kings named Henry (Henry I and Henry II) each ruled for an identical 35 years. Such perfect numerical synchronization of reign lengths across non-sequential monarchs is a profound anomaly.

Even more striking are the combined reigns: The total reign duration of the Lancaster Henrys and the total reign duration of the Tudor Henrys are both exactly 62 years.

This level of numerical precision in reign lengths and combined dynastic durations, especially across periods separated by significant historical upheaval, goes far beyond the realm of coincidence. It is the hallmark of a system where dates and periods were carefully calculated and assigned.

Conclusion: History by the Numbers

The consistent appearance of these structural and numerical anomalies—the Edwardian algorithm, the block programming of dynasties, the triple-king pattern, and the identical reign durations—provides compelling evidence against the organic evolution of English royal history. Instead, it supports the thesis that large segments of this history were meticulously designed and fabricated. The English monarchy, it seems, was not simply a succession of rulers, but a carefully constructed narrative, programmed with secret patterns to present an idealized and orderly past.