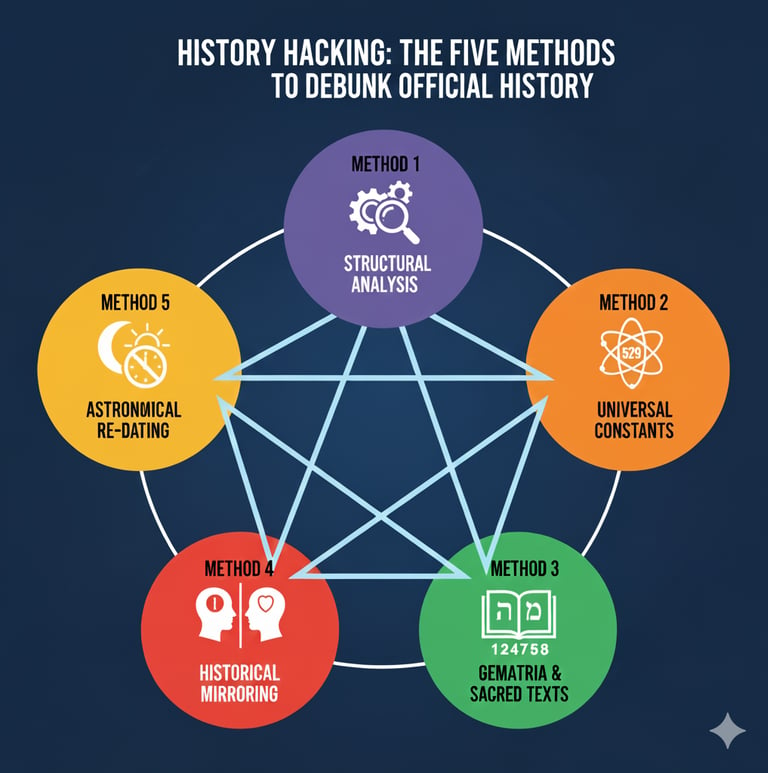

History Hacking: The Five Methods to Debunk Official History

This article introduces History Hacking, an approach that challenges official historical narratives by treating them as constructed datasets rather than immutable facts. It outlines five key analytical methods. It describes how to uncover hidden algorithms (Structural Analysis), find linking numerical constants (Universal Constants), decode sacred text influences (Gematria & Sacred Texts), identify narrative duplicates (Historical Mirroring), and re-evaluate astronomical events (Astronomical Re-Dating). The goal is to expose history as a potentially fabricated timeline, urging critical analysis over blind acceptance.

9/24/20255 min read

For centuries, we have treated the official historical narrative as an immutable record of the past. But what if there are glitches, hidden algorithms, and universal constants that, once found, reveal the entire system is an artificial construct?

This is the world of History Hacking. It is a revolutionary approach that treats the historical timeline not as a sacred text, but as a dataset to be interrogated. Using History Hacking I have explored numerous glitches in the matrix of our past, from repeating timelines to secret numerical codes. Now, we pull back the curtain to reveal the five key analytical methods used to deconstruct this official history. This is your toolkit for seeing the past in a way you never have before.

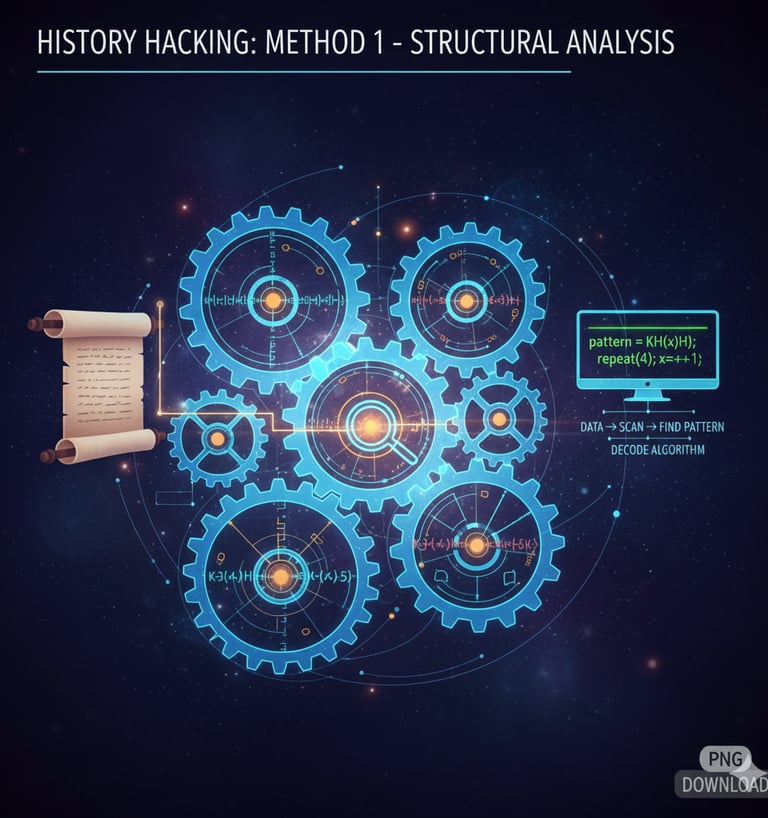

Method 1: Structural Analysis (Finding the Algorithm)

The Concept: This method treats historical data, such as king lists or chronological event logs, as a sequence of information to be scanned for non-random patterns. Real history is chaotic and unpredictable. A constructed history, however, often contains the clean, repeating logic of a computer program.

How it Works: You search for repeating, symmetrical, or mathematically growing sequences that are statistically impossible to have occurred by chance. The goal is to find the underlying algorithm that was used to generate the historical narrative.

The Prime Example: The German King List from 911-1313 AD. The succession of kings in this 402-year period is not random. It follows a perfect, growing algorithm of KH(x)H, which repeats four times. This is layered with another perfect structure: three distinct 113-year dynastic cycles, each initiated by a king of the same name.

The Takeaway: If a 400-year history of war, politics, and succession looks as clean and predictable as a line of code, it was almost certainly programmed.

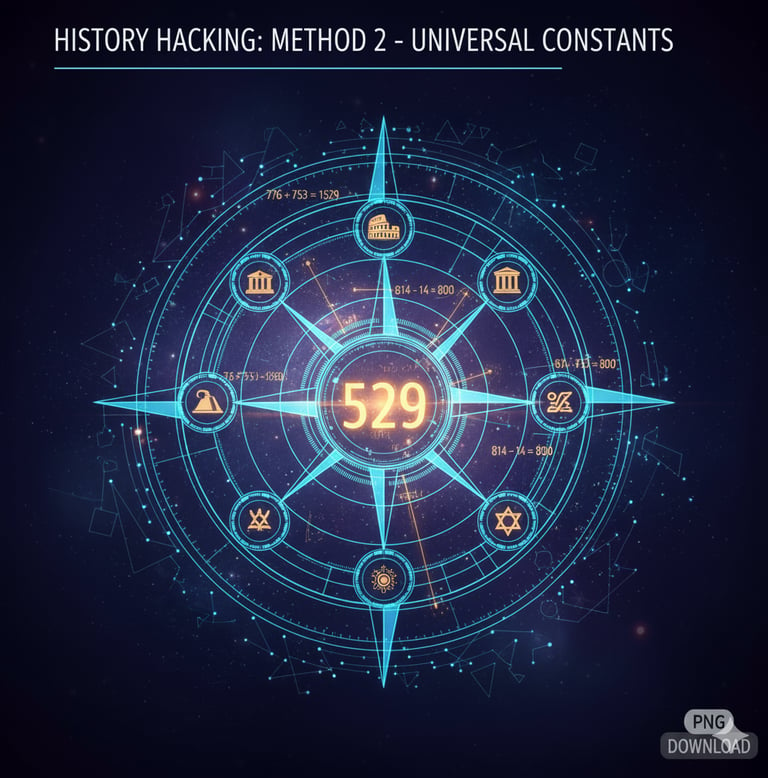

Method 2: Universal Constants (Numerical Anchoring)

The Concept: This method looks for recurring, fixed numbers that act as "universal constants," either in the mathematical construction of the timeline or in the narrative structure of historical events. These constants suggest that different parts of history were not independent but were created as part of a single, unified system.

How it Works: This method has two approaches. The first is finding chronological constants—master numbers that mathematically link different calendars and eras together. The second is finding narrative constants—fixed time intervals that separate parallel events or biographies, suggesting one story was used as a template for another.

The Prime Examples: The master chronological constant is the number 529. The start dates of the Greek, Roman, Babylonian, and Jewish eras can all be derived from simple formulas involving 529. The master narrative constant is the 800-year cycle. The lives of Romans Julius Caesar and Augustus are mirrored with astonishing precision by Charlemagne and Charles V exactly 800 and 1600 (2 x 800) years later.

The Takeaway: Universal constants, whether in the calendar or in the story, are the fingerprints of a unified design.

Method 3: Gematria & Sacred Texts (The Biblical Blueprint)

The Concept: This method explores the possibility that secular history was written to reflect the sacred numerology of religious texts. By embedding biblical codes into a dynasty's timeline, the constructors could grant that dynasty divine legitimacy and a pre-ordained right to rule.

How it Works: Using gematria (the system of assigning numerical values to letters), you calculate the numerical value of a foundational verse, like Genesis 1:1. You then search for those numbers, or their prime factors, in the chronologies of royal dynasties—their reign lengths, their life spans, and the intervals between key events.

The Prime Example: The Bible Code in History. The Hebrew gematria value of Genesis 1:1 is 2701, which is the product of the prime numbers 37 x 73. These two numbers then appear repeatedly and systematically throughout the reigns of the Merovingian Kings, structuring their entire history around this divine blueprint.

The Takeaway: When a king's history perfectly mirrors a sacred code, it's far more likely that the history was written to fit the code, not the other way around.

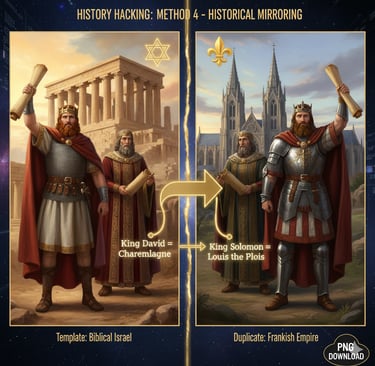

Method 4: Historical Mirroring (The Template Method)

The Concept: This method moves beyond general similarities to find detailed, one-to-one narrative parallels between two different historical periods. It suggests that a single "story template" from a revered source—most often the Bible—was used as a direct blueprint to construct the history of a later kingdom, thereby legitimizing it as a successor to God's chosen people.

How it Works: You map the sequence of rulers and key events from one history (e.g., ancient Israel) and compare it directly to the sequence in another (e.g., the Frankish Empire). You look for direct correspondences in ruler archetypes, major political events, and national narratives.

The Prime Example: The history of the Frankish Empire is a direct mirror of the biblical history of ancient Israel. The first three great Carolingian rulers perfectly match the first three kings of Israel: Pepin the Short mirrors Saul; his son Charlemagne mirrors King David; and his son Louis the Pious mirrors King Solomon. Following this, the division of the Frankish Empire at the Treaty of Verdun mirrors the division of Israel into two kingdoms.

The Takeaway: When the history of a Christian empire perfectly mirrors the history of biblical Israel, it's likely that the Bible was used as a direct script for writing that history.

Method 5: Astronomical Re-Dating (The Eclipse Challenge)

The Concept: Ancient history is heavily anchored by astronomical events, especially solar eclipses. However, official dating of these events relies on a highly speculative physical parameter called Delta T, which accounts for the supposed slowing of the Earth's rotation over millennia. Its value in antiquity is not precisely known and is extrapolated backwards. This method challenges those extrapolations.

How it Works: Instead of accepting the speculative Delta T values, this method re-calculates the visibility of ancient eclipses assuming a more stable Earth rotation, consistent with modern observations. This re-dating often shows that eclipses described in ancient texts could not have been visible at the time and place historians claim.

The Prime Example: The re-dating of the eclipses described by the historian Thucydides during the Peloponnesian War. Official history dates this war to the 5th century BC. However, without the speculative Delta T, the astronomical data shows that these specific eclipses were actually visible in Greece in the 7th and 8th centuries AD, suggesting the entire war is a medieval event misplaced in antiquity by over 1100 years.

The Takeaway: If the stars don't align with the official dates without speculative "fudge factors," the dates are likely wrong.

Conclusion: Become a History Hacker

These five methods are more than just analytical tools; they are a new lens through which to view the past. They reveal that the historical record we accept without question is filled with mathematical impossibilities, narrative duplicates, and artificial symmetries. The official story of our world may not be a story of what happened, but a story that was made to happen—on paper.

The ultimate lesson of History Hacking is one of empowerment. Do not take history at face value. Question the dates. Analyze the patterns. Look for the glitches. The past is a puzzle, and you now have the tools to begin solving it.