The Algorithmic Kings: Deconstructing the Royal List of the Holy Roman Empire (911-1313)

The royal succession in the Holy Roman Empire from 911 to 1313 AD was not a product of historical chance but a deliberate, artificial construction. This article highlights a repeating and growing mathematical pattern, CH(x)H (Conrad, Henry, 'x' other kings, Henry), that defines the sequence of rulers. Furthermore, it reveals a second structural layer: the timeline is divided into precise 113-year cycles, each initiated by a King Conrad who ushers in a new dominant dynasty (Saxon, Frankish, and Swabian). The argument is strengthened by the fact that the key names of the algorithm (Konrad, Heinrich) appear exclusively within this 403-year period, suggesting the entire list is a fabricated historical narrative rather than an authentic record.

ESSENTIALS

9/14/20253 min read

History, we are taught, is a messy and unpredictable affair. It’s a story written by chance, ambition, and the chaos of human conflict. But what if, hidden within the official record, there lies a perfect, mathematical order? What if the succession of kings in one of Europe's most powerful empires followed a secret algorithm, a blueprint so precise that it defies all notions of chance?

The list of kings in the Holy Roman Empire from 911 to 1313 AD is not a random historical record. It is a deliberate, artificial construction that follows a clear and repeating formula. Using a method called Structural Analysis, which searches for repeating and growing patterns in historical data, we uncover a system that seems more at home in computer science than in a history book.

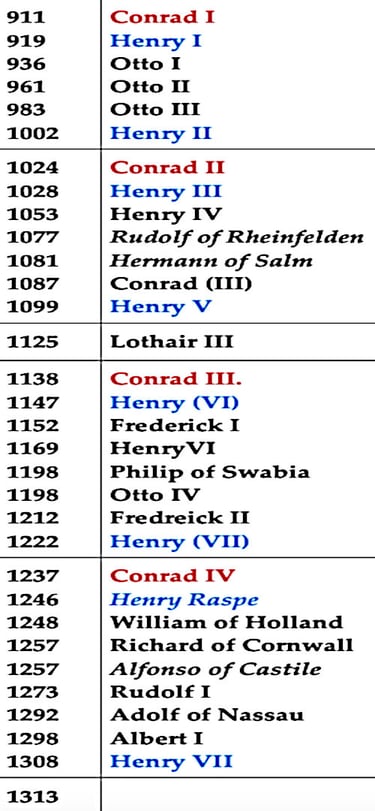

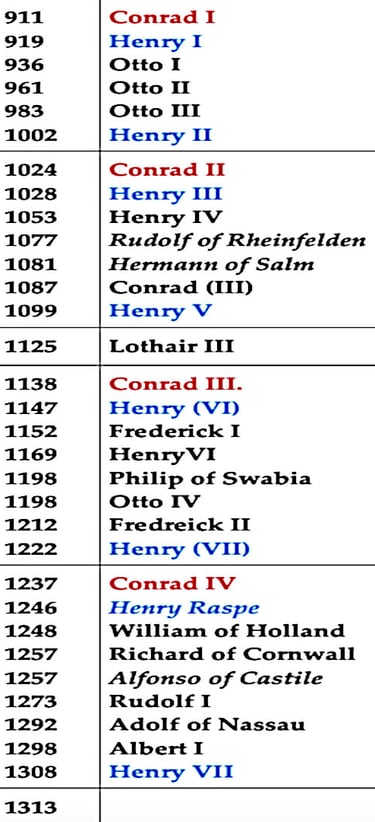

The Royal Algorithm: CH(x)H

When you analyze the names of the German kings between 911 and 1313, a startling pattern emerges. The entire 403-year period (inclusive counting as was customary in the Middle Ages) is built on a simple, repeating algorithm that combines a fixed sequence with a growing variable.

The base pattern is:

C (a king named Conrad) -> H (a king named Heinrich) -> (x) (a list of 'x' kings with other names) -> H (another king named Heinrich)

This pattern, CH(x)H, repeats itself four times. What makes it a "growing" pattern is that the value of 'x' (the number of kings in the middle) increases by one with each repetition.

First Cycle: CH(3)H

Second Cycle: CH(4)H

Third Cycle: CH(5)H

Fourth Cycle: CH(6)H

This level of algorithmic precision in a royal succession spanning four centuries is statistically impossible as a product of chance. It is, as the author states, a clear and recognizable pattern that points to a manufactured history.

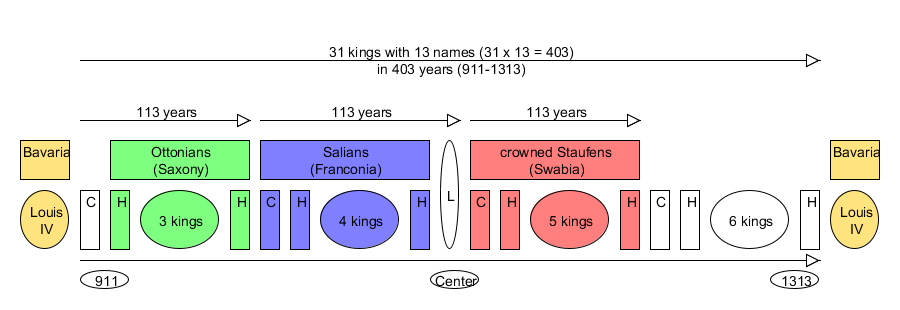

The 113-Year Dynastic Clockwork

As if one layer of artificiality wasn't enough, the system contains a second, equally precise structure built on the number 113. The period from 911 to 1250 is perfectly divided into three distinct sections, each lasting exactly 113 years - with a uniform start of the year on March 25 (and not January 1), as was customary in the Middle Ages.

Each of these 113-year blocks is not only mathematically precise but also serves a specific narrative function. It is initiated by a King

Konrad, who ushers in a new ruling dynasty representing one of the major German stem duchies.

911 AD: Conrad I begins the first 113-year period. His reign paves the way for the

Saxon Ottonian dynasty, who dominate this era.1024 AD: Exactly 113 years later, Conrad II begins the second period. He founds the

Frankish Salian dynasty, who dominate the next 113 years.1137 AD: Another 113 years later, Conrad III begins the third period. He is the first king of the

Swabian Staufer dynasty, who dominate until 1250.

The structure is flawlessly symmetrical. The three main German tribes - Saxons, Franks, and Swabians - are given their own 113-year era, each kicked off by a king of the same name. The remaining duchies are also perfectly placed: a king named Lothair (representing Lotharingia) is positioned exactly in the middle of the entire 403-year structure, while the Bavarians (in the person of Louis IV) perfectly frame the system, ruling immediately before 911 and immediately after 1313.

A Closed System: Names That Don't Mix

The final piece of evidence for this being a fabricated system is perhaps the most compelling. The names that define the structure—Conrad and Henry—appear as royal names only within the 911-1313 timeframe. Before and after this period, they are absent from the list of German kings.

Conversely, the names that frame the system—Charles and Louis—appear as rulers only outside of the 911-1313 period. This mutual exclusivity creates a perfectly sealed "narrative block," suggesting that the historians who constructed this timeline assigned specific names to specific eras according to a strict set of rules.

Can this be a coincidence? A 403-year period of history defined by a repeating, growing algorithm, subdivided into perfect 113-year dynastic blocks, and framed by names that only appear outside of its boundaries. The evidence points not to the chaotic ebb and flow of real history, but to the clean, symmetrical lines of a deliberately designed architecture.