The Salvation History of the Franks: The Old Testament as a Blueprint for the Carolingian Saga

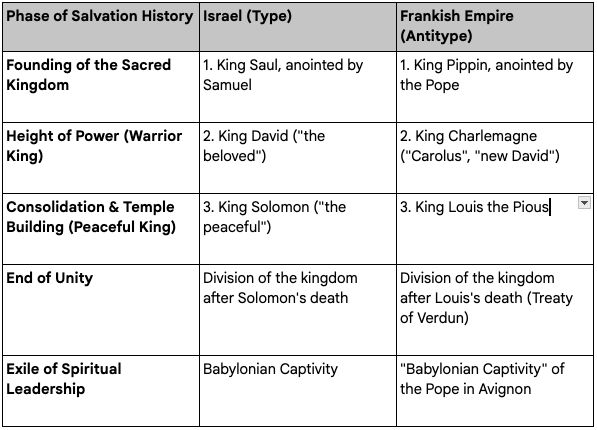

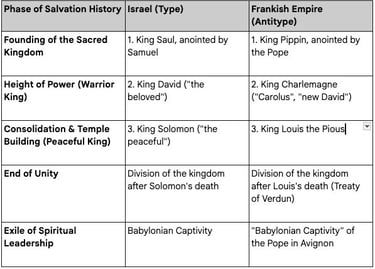

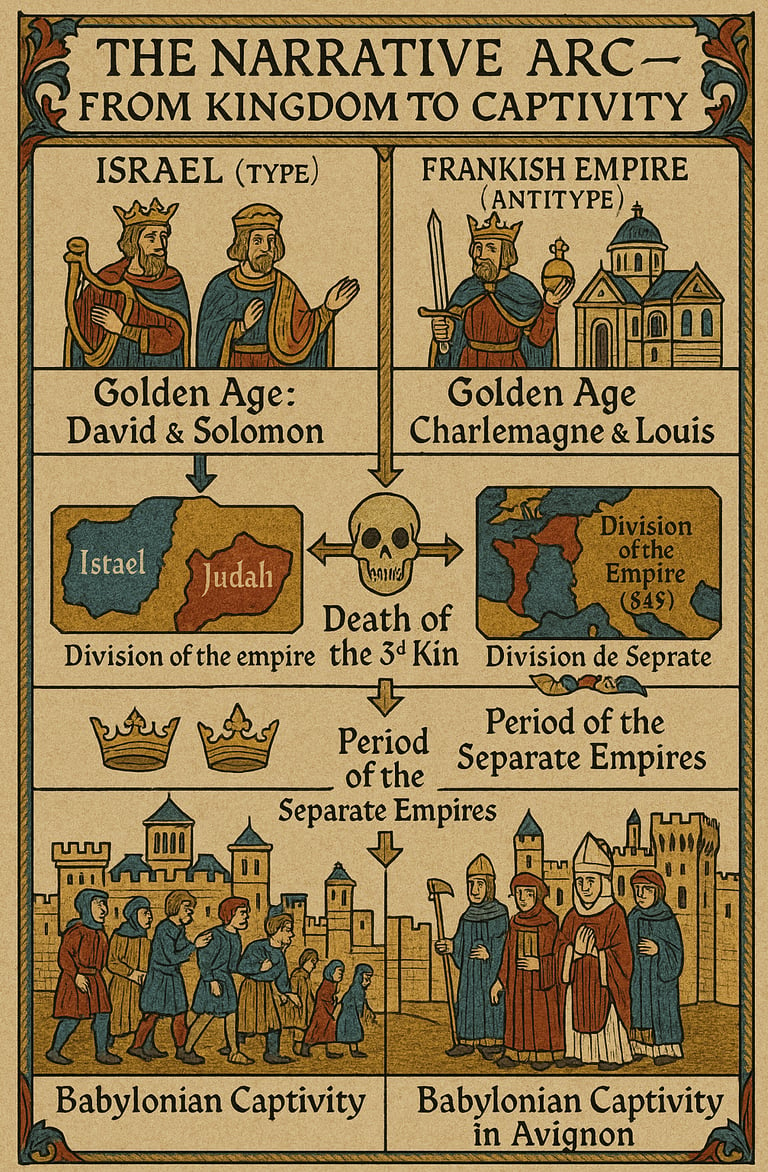

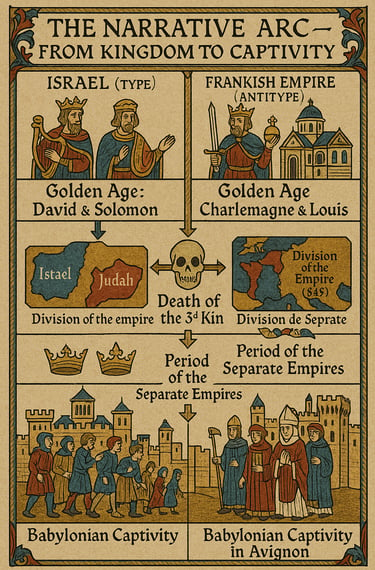

The historiography of the Franks was a deliberate theological project designed to legitimize the Carolingian Empire by framing it as a typological fulfillment of the Old Testament. Using the hermeneutical method of typology, the narrative intentionally parallels key figures and events from Israel's history. The first three Carolingian rulers—Pippin, Charlemagne, and Louis the Pious—are presented as antitypes to the Israelite kings Saul, David, and Solomon, respectively. This parallel extends to later events, such as the division of the Frankish Empire and the Avignon Papacy, which mirror the schism of Israel and the Babylonian Captivity. The ultimate purpose of this construction was to create a foundational myth that secured the new European order a sacred place in divine salvation history.

ESSENTIALS

8/24/20253 min read

The writing of history in the early Middle Ages was more than a mere chronicle of events. It was a profound theological and political project aimed at securing a place for the Frankish Empire in the divine plan of salvation. At the heart of this endeavor was the creation of a "Christian Old Testament" for Europe, in which the Franks would assume the role of the chosen people of Israel.

Typology as the Hermeneutical Key

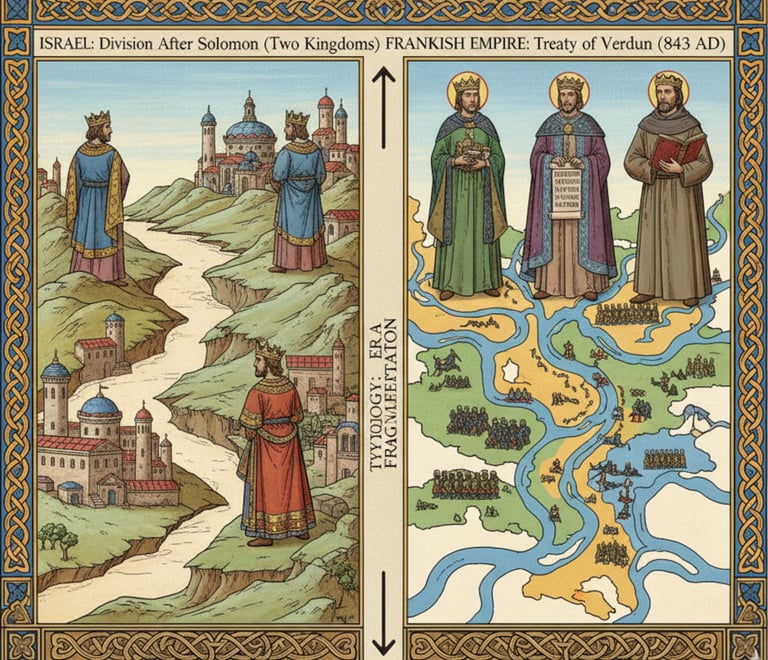

The intellectual foundation for this monumental undertaking was provided by typology, a hermeneutical method that was ubiquitous in the Middle Ages. In this approach, individuals and events from the Old Testament (the typos or type) are understood as prefigurations of a later, fulfilling reality in the New Testament and Christian salvation history (the antitypos or antitype). The Carolingian saga is the consistent application of this principle to political history, intended to bestow an unchallengeable, sacred legitimacy upon the Frankish Empire.

The Carolingians as the Antitype of Israel

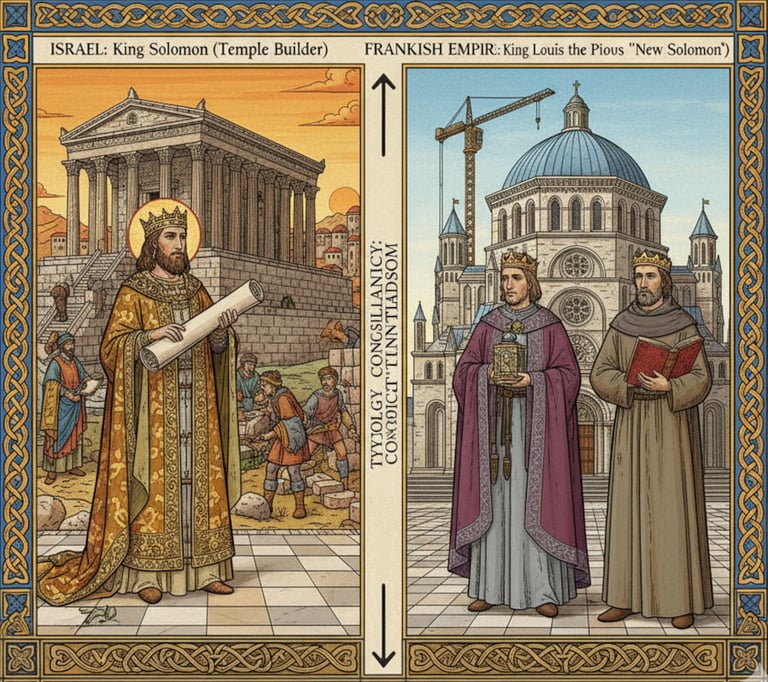

The core of this typological construction is the exact parallel drawn between the first three kings of the united kingdom of Israel and the first three rulers of the Carolingian dynasty.

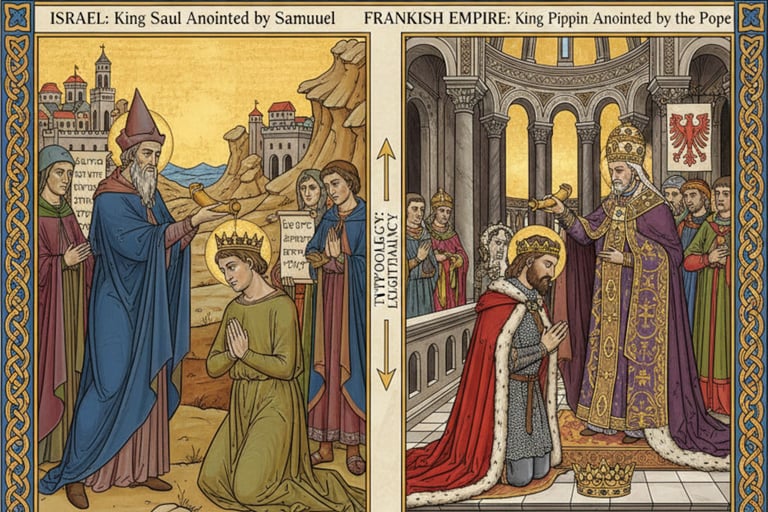

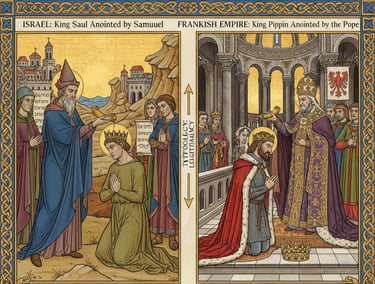

Pippin as the new Saul: Just as Saul was the first king of Israel anointed by the high priest (Samuel), Pippin the Younger was the first Carolingian king whose rule was sacredly legitimized by the anointing of the Pope—the high priest of the new Christian order. In both narratives, an old, weak form of rule (the Judges in Israel, the Merovingian "shadow kings") is replaced by a divinely willed monarchy.

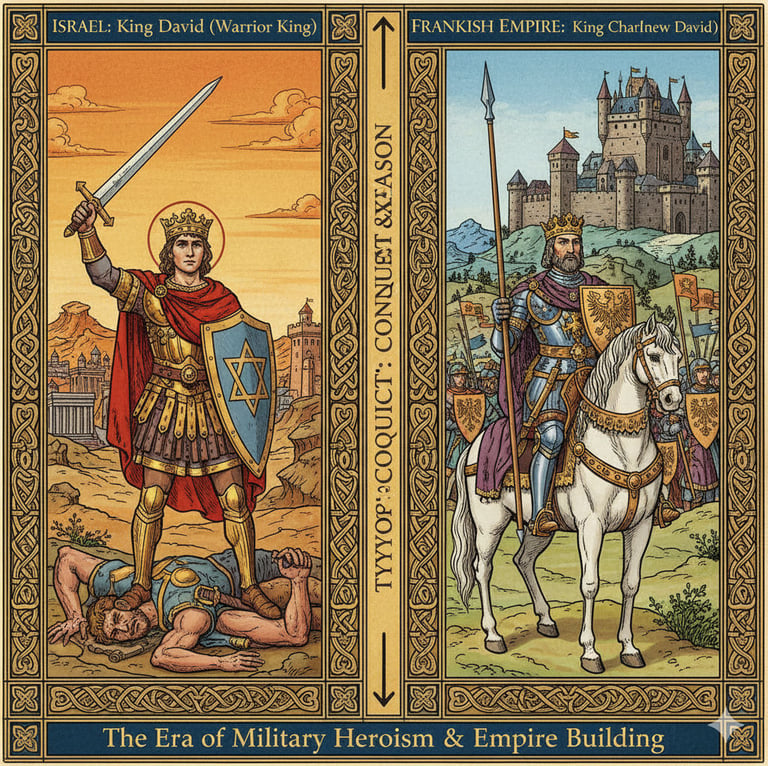

Charlemagne as the new David: King David was Israel's greatest warrior hero, who expanded the kingdom to its maximum size. Charlemagne is depicted in precisely this image; his military campaigns mirror David's conquests. The connection was made explicit: at his court, Charlemagne was addressed as the "new David". Furthermore, the name Carolus itself can be understood as a scholarly Latin translation of the Hebrew name David—"the beloved" or "darling" (from Latin carus + diminutive -olus).

Louis the Pious as the new Solomon: The warrior-king David was succeeded by his son Solomon ("the peaceful"), whose reign was marked by internal consolidation, wisdom, and the construction of the Temple in Jerusalem within seven years. Louis the Pious is presented as his antitype. His reign focused on the internal order of the empire. The building conceived as the "new Temple of Solomon", the Palatine Chapel in Aachen, had already been built by Charlemagne - within seven years, of course..

The Parallel Continues

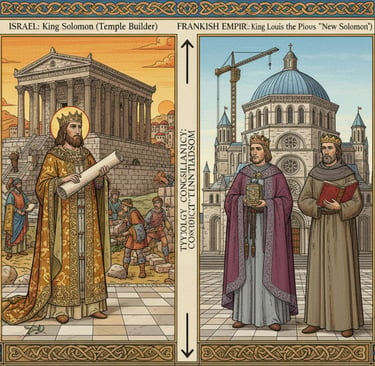

The robustness of this model is demonstrated by the fact that it does not end with the third king. The entire subsequent history of the Frankish Empire and its successors into the late Middle Ages appears to be shaped by this biblical blueprint.

The Division of the Empire: The partition of the Frankish Empire after the death of Louis, formalized in the Treaty of Verdun (843), precisely mirrors the division of Israel into a northern and a southern kingdom after the death of Solomon.

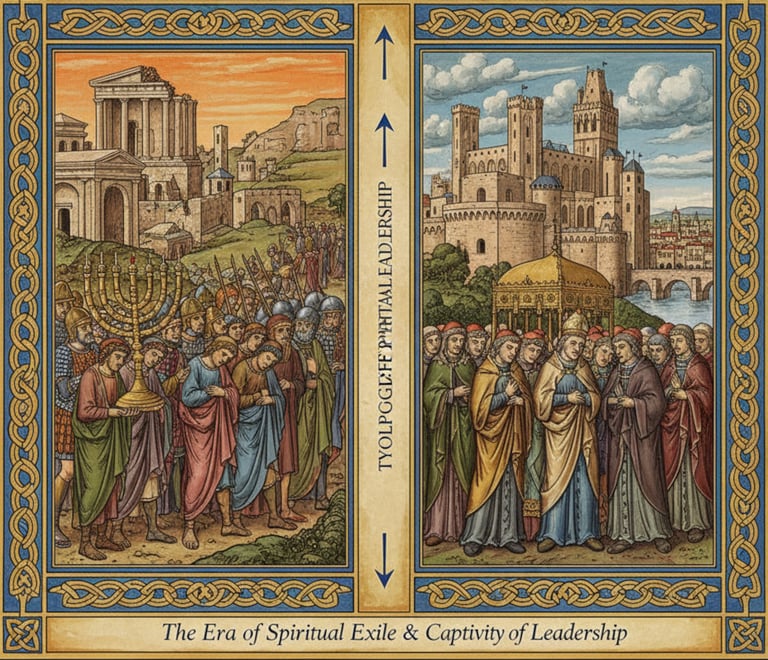

The Babylonian Captivity: The most compelling evidence for the conscious application of this scheme is the labeling of the Avignon Papacy (1309–1377) as the "Babylonian Captivity" by contemporaries like Petrarch - according to official history. This was not a later comparison made by historians; it proves that the actors of the 14th century themselves thought in these typological parallels. They saw themselves as participants in an ongoing salvation history, in which the story of the Franks continued and fulfilled that of the old chosen people.

The following table summarizes these typological correspondences.

Conclusion

The Carolingian saga was therefore a theological project that assigned the new European empire a firm place in the divine plan of salvation. Charlemagne was not a man of flesh and blood, but a myth. He was the central heroic figure of a grand founding epic, created to give the emerging medieval world order a divine legitimacy and a venerable past.